Childlessness and Later Fertility

Here’s another later-fertility story from the Pew Research Center. Last month they confirmed our suspicion that there are indeed more older moms around. This month they report that fewer women are having kids. Both reports resonate significantly with the recent 50-year anniversary of the birth control pill, confirming predictable outcomes.

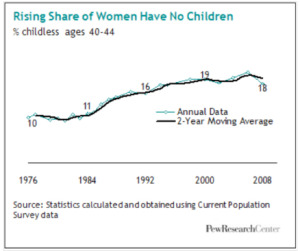

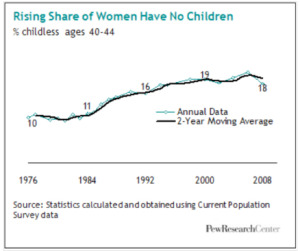

But the data are not entirely clear cut. For instance, the new report begins with an oddity. The headline reads “Childlessness Up Among All Women; Down Among Women with Advanced Degrees.” The lead sentence tells us that “Nearly one-in-five American women ends her childbearing years without having borne a child, compared with one-in-ten in the 1970s.” It turns out, they are comparing fertility data about women ages 40 to 44 across 30 years, and the “nearly one-in-five” is specifically 18 percent.

What’s odd is that the graph the authors provide (though not the discussion) indicates that the rate of childlessness in this age group in 2000 was 19 percent.  So, it would have been just as correct for the headline to read “Childlessness Down Among All Women.” Or “Childlessness Fairly Steady For Past 15 Years,” since, as the graph also shows, the big rate jump occurred between 1984 and 1992, when the rate went from 11 percent to 16 percent. So that change is not exactly news.[1] Data are mobile, to paraphrase Rigoletto.[2] Since headlines are often all that people take in, care in contextualizing them is important, especially about key issues like fertility and family.

So, it would have been just as correct for the headline to read “Childlessness Down Among All Women.” Or “Childlessness Fairly Steady For Past 15 Years,” since, as the graph also shows, the big rate jump occurred between 1984 and 1992, when the rate went from 11 percent to 16 percent. So that change is not exactly news.[1] Data are mobile, to paraphrase Rigoletto.[2] Since headlines are often all that people take in, care in contextualizing them is important, especially about key issues like fertility and family.

Another complication comes in the use of the word “childless.” The study looks at biological childlessness, and does not include step- or adopted kids. So its focus is on the biological productivity of children by women, not on their experience or construction of family. Many parents in the not-included categories would take exception to being called childless. That’s not what the study was about, it turns out, but the title is imprecise and the terrain is muddy.

And of course “childless” itself is a fraught term. People who choose not to have kids or who couldn’t have kids but don’t want to dwell on the fact often prefer the word “childfree.” As ever, data-mining can be a minefield.

As you will have remarked by now, there are many back stories in play here, especially on the explanatory front.

Causes of trend?

• A. Increase in Voluntary Childlessness: due to birth control, increased career options and lessened social pressure, increasing numbers of women and men choose not to have kids.

• B. Increase in Delay Leading to Infertility: due to those same factors and others, many women put off trying for kids until later and some of them wait too late to have kids with their own genetic material.

(The Pew researchers cite one study of 2002 data that found among those who defined themselves as never going to have kids, these explanations split the group about half and half.)

• C. Some Are Only Temporarily Childless: they will yet have kids – either as standard issue or via egg donation or egg freezing. This category isn’t dealt with in the study.

Fertility choices of women 40 to 44 today differ from their seventies counterparts’:

Point B morphs into point C when another premise of the study–that women ages 40 to 44 are at the end of their childbearing years–is put under the microscope.

There are at least two points at issue here:

1. That 44 is the end of fertility. That was a fair working premise for the vast majority of women until recently. But whereas in 1980 only 60 previously childless American women had their first babies in the 45+ range, in 2008 2,036 women in that age range had their first baby, 34 times as many (out of a total 7,666 babies born to women in this age group, up from 1,200).

Birthrate-wise that’s an increase from 0.0 to 0.2 births per thousand women ages 45 to 49 having a first birth and from 0.2 to 0.7 among women ages 45 to 49 overall.[1] It’s still a very small group, but it’s growing at a great rate. So the report operates under the cloud of a kind of a willed delusion. Yes, it’s true that most women who don’t have kids the usual way won’t have any, but it’s also true that women who have no kids through their mid 40s have a lot more money to spend on fertility treatments than their fecund younger sisters and increasing numbers will be successful. That money, and the cultural clout that goes with it, are part of the reason they waited. And this growing option should be part of the discussion.

2. That childless 40-year-olds in 2008 are as unlikely to have kids as their counterparts in 1978. They’re not. The use of 40- to 44-year-olds as a group with the same standard fertility prospects is very problematic because it’s physically untrue (one study indicated that roughly 66 percent are fertile at age 40, 50 percent at age 41, and then a quick downhill to 13 percent at 45).[4] In the past however, it may have seemed true, for social reasons. Back in the day there was a lot of pressure on women to marry and have kids young, so very few women who intended to have kids entered their 40s without any.

But now many women do delay their first child til 40 and beyond, and many of those women will yet have kids — which means they will leave the realm of the “childless” after their 40th birthday in larger proportion than women did in the past. And indeed, in 2008 the group of mothers 40 and up was the only group to buck the downward recessionary birth trend and show an increased birth rate (up 4 percent). This too should be part of the discussion.

There’s plenty more to say on all this, it’s complicated, and good data are hard to find– but this is the morphing world we live in and we have to keep track of lots of dynamics at once when talking about contemporary fertility, which is both highly politicized and highly personal. The Pew report offers a nice opportunity to open up the discussion of the realities of modern fertility, but let’s look hard at the data before we accept the headline analysis. There’s a lot still to be determined.

I’ll be writing on the education angle later.

This post appeared first on RH Reality Check.

[1] Interestingly, the CPS data seem to differ from the National Survey of Family Growth data cited in the Pew report’s footnotes, which gives 15% as the total childless figure for 2002 (6 percent voluntary, 6 percent involuntary, 2 percent temporary, 1 percent unaccounted for) and 12 percent for 1982. Abma, Joyce C., and Gladys M. Martinez. “Childlessness Among Older Women in the United States: Trends and Profiles.” Journal of Marriage and Family, 68:4. (2006).

[2] It would be interesting to see a graph of this trend for the whole 20th century – it’s been so up and down on the fertility front. Expanded graphs often enrich the story, but the data is not always available.

[3] Though women 50-54 are also included in the numerator since there are so few.

[4] They are linked here because that’s the way the statistics are gathered, in five-year groups.

So, it would have been just as correct for the headline to read “Childlessness Down Among All Women.” Or “Childlessness Fairly Steady For Past 15 Years,” since, as the graph also shows, the big rate jump occurred between 1984 and 1992, when the rate went from 11 percent to 16 percent. So that change is not exactly news.[1] Data are mobile, to paraphrase Rigoletto.[2] Since headlines are often all that people take in, care in contextualizing them is important, especially about key issues like fertility and family.

So, it would have been just as correct for the headline to read “Childlessness Down Among All Women.” Or “Childlessness Fairly Steady For Past 15 Years,” since, as the graph also shows, the big rate jump occurred between 1984 and 1992, when the rate went from 11 percent to 16 percent. So that change is not exactly news.[1] Data are mobile, to paraphrase Rigoletto.[2] Since headlines are often all that people take in, care in contextualizing them is important, especially about key issues like fertility and family.