Part of the background to the current confusion about how long fertility lasts is the fact that there is very little good data. (Related stories: A B C)

As I noted in Ready, nobody knows exactly at what rate fertility declines today or if it’s the same average rate all over, because doctors can’t mandate that a big group of people have unprotected sex constantly for the sake of an experiment. Most people use some form of birth control unless they are trying to get pregnant (including restraint and withdrawal as well as pills, condoms, etc.).*

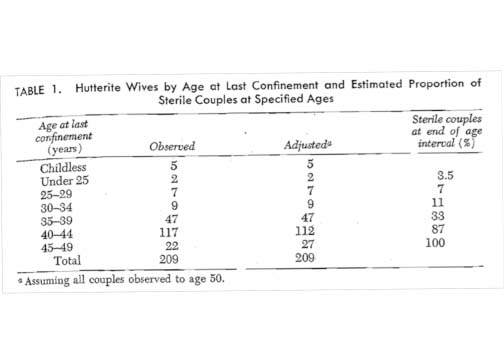

The closest thing to a thoroughly controlled experiment of women’s fertility so far involved a Protestant religious sect called the Hutterites, pre-1950. The Hutterites of the period essentially tried to have as many kids as they could, year in and year out, as a religious duty, and the community supported all children equally so having more didn’t draw down the family resources. A study based on Hutterite data indicated that the infertility rate (deduced from when each woman had her last confinement) was 3.5 percent at 25, 7 percent at 30, 11 percent at 35, 33 percent at 40, 50 percent at 41 and 87 percent at 45. Thirteen percent of them had their last baby between 45 and 49, and nobody had a baby after 49. The average woman in this group had eleven babies! (And unlike in the general population, the women tend to die earlier than the men.)

For your reference, here are the relevant charts from Christopher Tietze’s report on the study, with some background info:

“[The] report is based on the histories of 209 Hutterite women who married prior to the age of 25 years, married only once, and who were living with their husbands at age 45.Three out of 4 women in this group, 151 in all, were observed in the married state up to or beyond the age of 50 years, while the remaining 58 were observed to some point between 45 and 50 years of age.

“Of the 209 women in the study, 5 had no children.A sterility ratio of 2.4 per cent is low but not extraordinary, considering that the average age at marriage was 20.7 years.The remaining 204 women had experienced from 2 to 16 pregnancies excluding those terminating in fetal death.The total number of confinements was 2009, corresponding to averages (means)_ of 9.6 per woman and 9.8 per mother. These 2009 pregnancies resulted in 1989 single births and 20 pairs of twins. “

The “adjusted” column estimates “the number of additional confinements that would have occurred if all women had been observed to age 50” (based on the percentage among those who were).

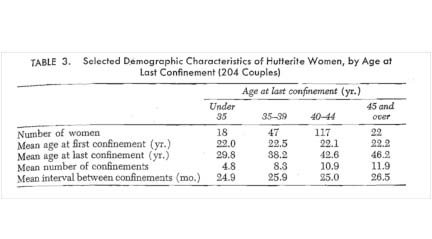

C. Tietze, Table 3, “Reproductive Span and the Rate of Conception among Hutterite Women,” Fertility and Sterility 8 (1957): 89-97.

Table 3 looks at the statistics on age at last confinement (or birth) for the group, not including the 5 women who had no confinements.

These infertility numbers may have been low relative to the general population at the time, and they may be low now, but we can’t prove that because the records of any group of people today would be skewed by the many forms of birth control in use. Besides that, unless people are impelled by a religious enthusiasm like the Hutterites, there’s no way to guarantee that even a totally “natural” population won’t skew the data by simply exercising restraint in the bedroom at the prospect of too many children.

One researcher I spoke with noted that, given that no rigorous studies have been done on fertility in women’s forties, it’s also possible that the onset of age-based infertility might have occurred earlier among the Hutterites than it would among the rest of the population, due to the wear and tear on the women’s reproductive systems from having had so many babies. But there is no direct evidence of that.

While we can’t prove through equivalent studies that contemporary wombs are (or your womb in particular is) more or less fertile than the wombs of the Hutterites, there is no reason to think that the effect of age on fertility is any worse now than it was 100 years ago.

Some recent results do corroborate the general trend of the Hutterite study for women 35 to 39. Data collected at seven European natural family-planning centers in the late 1990s (the European Fecundability Study) indicate that about 90 percent of women not already known to be infertile due to pre-existent issues like endocrinal disorders or surgery who try to conceive between ages 35 and 39 will become pregnant within two years. That’s if they use natural family-planning methods (charting temperature and cervical mucous to more accurately predict when ovulation happens and to shorten time to conception) and have sex at least two days per week. [1] Roughly 82 percent will become pregnant within one year.[2]

Is Infertility on the Rise?

The many stories circulating about fertility problems and treatments may give you the impression that the incidence of infertility is rising. A 2013 CDC report says that infertility has actually declined in the past thirty years. If you’re confused about fertility, it’s probably because you’ve been paying attention—the messages out there are mighty mixed.

Though the use of fertility treatments is rising, there’s no evidence that the intrinsic span of women’s fertile years has changed much over time. While advancing treatment options can expand the span for some, the blockage of fallopian tubes brought on by pelvic inflammatory disease or endometriosis can impair it for others. Then there’s the male infertility element.

So if women aren’t more infertile now than in the past, why are the numbers of visits to fertility doctors rising? In part because more people start trying for children later in life, at ages when fertility rates have always been lower. In addition, more fertility treatments are now available so more people seek them out, and there are more fertility doctors.

That last item may seem to argue circularly. But while the rise in the number of fertility doctors responds for the most part to a rise in demand (caused by the first two points on that list), it is also a response to the potential for profit in this area. Fertility clinics are an enormous boon to the infertile, but they are, after all, businesses as well—as Debora Spar points out in her book The Baby Business—and businesses seek to expand the market for their services where possible. The reigning mood of fertility anxiety encourages women to visit doctors at the slightest sign of difficulty.

Doctors need customers (the average fertility clinic needs to perform three hundred to four hundred IVFs at about $12,000 each to break even, and most are run for profit). Spar explores the complexity of the current fertility market—noting that, while doctors do work to get their clients good results, they may also profit from prescribing treatments that have a great likelihood of failure (like IVF for women who are unlikely candidates) but which couples will step up to pay for, sometimes repeatedly, because they live in hope. Sometimes the couples won’t take no for an answer, even when doctors try to dissuade them. And, of course, there’s always a chance that it will work, though that chance might be slight.

Doctors may also profit from prescribing unnecessary treatments to women in their mid-thirties who are driven to their offices by the anticipation of failure—some of them will really need help, and some of them might well get pregnant if they kept trying a little longer.

The tangled dynamics of the current fertility scene jumble together the parents’ desire for a child and the doctors’ and the pharmaceutical companies’ joint motives—both to assist potential parents and to make a profit. Some people are infertile early, and it’s hard to say firmly who fits that description, so it’s hard to blame doctors for taking an aggressive route. But we might hope they would avoid fanning the flames of anxiety and work instead to develop and convey clear information on fertility.

Sometimes they do the opposite, as seems to be the case with the kind of reporting involved in the recent story that “Women lose 90 per cent of ‘eggs’ by 30.” The headline implies a big fertility decline at 30 (a suggestion affirmed in interviews with the researchers) even though the data involved, on ovarian reserve, tell us nothing about the real rate of fertility of women at 30 or any age. In fact, in 2007, women 30 and older had 1,575,515 babies – more than one third of the babies born in that year. Keep that in mind the next time you read a scare-mongering infertility headline. Fertility does decline with age, but the point of onset of the decline does not itself decline at the clip suggested by such “studies.” In planning our family and work narratives, we’ve all got to take all the things that matter to us into account, and do our own research.

For more on this and related material, see Ready: Why Women Are Embracing the New Later Motherhood.

*A woman gets diagnosed as infertile when she and her partner have been trying consistently to conceive for a year, without success (barring a male infertility issue). Infertility is not the same as sterility, so infertile women might very well have children with technological assistance—or more trying. And then different people “try” with more or less efficiency, and that’s hard to gauge in a really rigorous way.

Pingback: Family to welcome 15th child; seeks reality TV show | theGrio