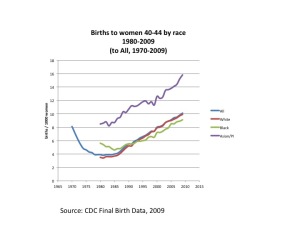

This week’s CDC detailed report on 2009 birth data, confirms their earlier finding that while births to women overall dropped 3 percent, births to women 40-44 continued to climb –- up 3% over 2008.

And leading the 40-44 climb were births to Asian women, which rose 6/10’s of a point (from 15.2 births / thousand to 15.8), while births to white women rose more slowly from 9.7 births/ thousand to 9.9, and births to black women rose from 8.9 births to 9.1. (Births to women 45-49 held steady for Asian women at 1.2/thousand, where they’re at 0.7 for whites, 0.6 for blacks, and 0.3 for Native Americans.)

Later births to Asian women have been ahead for decades, linked to rates of employment, time invested in and level of education, culture around work and work-purposed immigration.

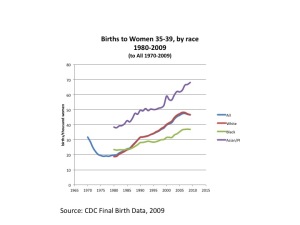

While the pattern for Asian women mirrored the rises and falls in births to all other groups of women in all other age bands, it differed in the 35-39 age band, where the rising trend continued upward.

While little research has been done on the topic by social scientists, one recent article does explore the income effects of Asian women’s work/family patterns, finding that as a group Asian women engineers and scientists (the group the writer had data on) take less time off from work when their kids are born than women of other races in the same fields with equal education. As a result of this greater time at work, they make more money over the long term than their female peers of other races and there is less of a wage gap between Asian men and women than between white men and women (Hispanic and black men and women also have lower wage gaps, because due to difficult economic circumstances, women’s work has long been an important part of the economic equation). (Greenman, 2011) This is relevant, in my view, not just as a pattern true of one culture (or set of linked cultures) but also for the model or basis for analysis it provides of potential work dynamics in all cultures.

Asian women may also, Greenman hypothesizes, be more likely to have grandparents living at home or nearby, to make it easier to return to work quickly, as well as a culture that doesn’t expect women to stop working when they have kids (and, I derive, may be less likely therefore to stigmatize childcare).

Clearly birth timing plays a role in here too, so we’ll be exploring that further in the near future.

Works Cited

CDC [Martin, Joyce A., MPH; Brady E. Hamilton, PhD; Stephanie J. Ventura, MA; Michelle J.K. Osterman, MHS; Sharon Kirmeyer, PhD; TJ Mathews, MS; and Elizabeth Wilson, MPH, Division of Vital Statistics] Births: Final Data for 2009.

Emily Greenman, “Asian American–White Differences in the Effect of Motherhood on Career Outcomes,” Work and Occupations February 2011 vol. 38 no. 1 37-67.