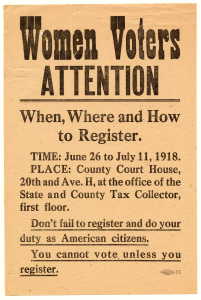

Today is Women’s Equality Day – the 93rd anniversary of the passage of the 19th amendment to the US constitution. My op-ed in today’s Houston Chronicle.

Women Voted in Texas in 1918 – from the Carey C. Shuart Women’s Archive & Research Collection, UHouston

How about full equity by the 100th anniversary in 2020?

Women’s suffrage Texas-style

Ninety-three years ago, when the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granting women the vote passed on Aug. 26, 1920, it was old news in Texas. Back then, Texas was at the forefront of positive political change for women; lately, we’ve had some setbacks.

In 1920, women had already been voting in Texas for two years, since Texas Woman Suffrage Association president and New Waverly native Minnie Fisher Cunningham and her co-agitators in 1918 had won women the right to vote in primaries. As the Democrats dominated Texas at the time, voting in the Democratic primary meant women had their say in state politics. As with any group, voting supplied the only means by which female citizens’ interests would be represented in policy-making.

In 1919, Cunningham was recruited by the National Woman Suffrage Association to lobby Congress, and her efforts paid off not just for her state but for her nation. Soon after, women won the national vote, and “Minnie Fish” as she was sometimes known, was among the founders of the national League of Women Voters.

Minnie Fish’s activism was born of bold ideas and hard experience. In 1901, she’d become one of the first women to receive a degree in pharmacy in Texas; she worked as a pharmacist in Huntsville for a year, but, finding that she made half what her male counterparts did and having other options, she quit, noting later that the inequity in pay “made a suffragette out of me.”

As we know, even after women got the vote, the pay-equity problem didn’t disappear; it’s still causing controversy here and nationally. Pay discrimination by gender became illegal in 1963, but that law has no teeth because there’s no oversight mechanism to ensure that people are paid fairly (in many businesses, it’s a firable offense to ask your coworkers what they’re paid) or for punishing in state court those who pay women less.

The recently vetoed Texas Lilly Ledbetter law didn’t directly require evidence that employees were paid fairly; it gave women the right to sue if discrimination was discovered to have occurred for more than 6 months after it began. But even that limited recourse seemed too threatening to some businesses. Will pay inequity make activists of enfranchised 21st-century Texas women, as it did with Minnie Fish? Stay tuned.

Fertility Politics

Terms like “woman suffrage” sound antique today, but the issues debated 93 years ago are very current. Though they may seem separate, reproductive rights, economic rights and voting rights are intimately linked and affect whole families, not women only.

Texas still is at the feminist forefront in some respects. For example, while neither New York nor Los Angeles has ever had a female mayor, and Chicago had one for one term in the early ’80s, Houston has had one for 14 of the past 32 years. But in other respects, we’re losing ground.

The 2011 cuts in poor women’s access to birth control through the drastic reductions in funding for the Women’s Health Program in Texas is predicted to result in thousands of unplanned births in the next year, at a cost of millions to taxpayers. Likewise, the expansion of “safety” rules in abortion clinics will drastically cut reproductive health services of all kinds to poor women across the state. Pharmacist Minnie Fish would not be proud of us. Unplanned births increase poverty levels by drawing young parents away from their educations into lifetimes of multiple low-wage jobs to support their kids, who themselves may repeat the cycle, and reduce the state workforce skills level when increased skills are needed.

When women who already have all the children they want are denied access to reproductive services, all the members of their families suffer. Older children’s hopes are diminished as each unsought new arrival depletes the resources of the group. And their parents, being busy and often uninformed about civic issues, are less likely to vote.

As Minnie Fisher Cunningham knew almost a century back, “social issues” (aka, women’s lives) are serious political and economic stuff. As proud heirs to the fairer world she helped realize, it’s the responsibility of Texans – male and female – to continue her tradition and move us forward.

The Minnie Fisher Cunningham papers live in the Carey C. Shuart Women’s Archive and Research Collection in the University of Houston Library.